U.S. wagering has fled the barn and won’t be corralled By: David McKee

It has been 15 months since the Supreme Court of the United States overturned the Bradley Act, making sports betting potentially legal across the land. The sports betting genie is out of the bottle, never to be reconfined. However, expectations that legalized sports wagering would sweep the country have proven somewhat exaggerated.

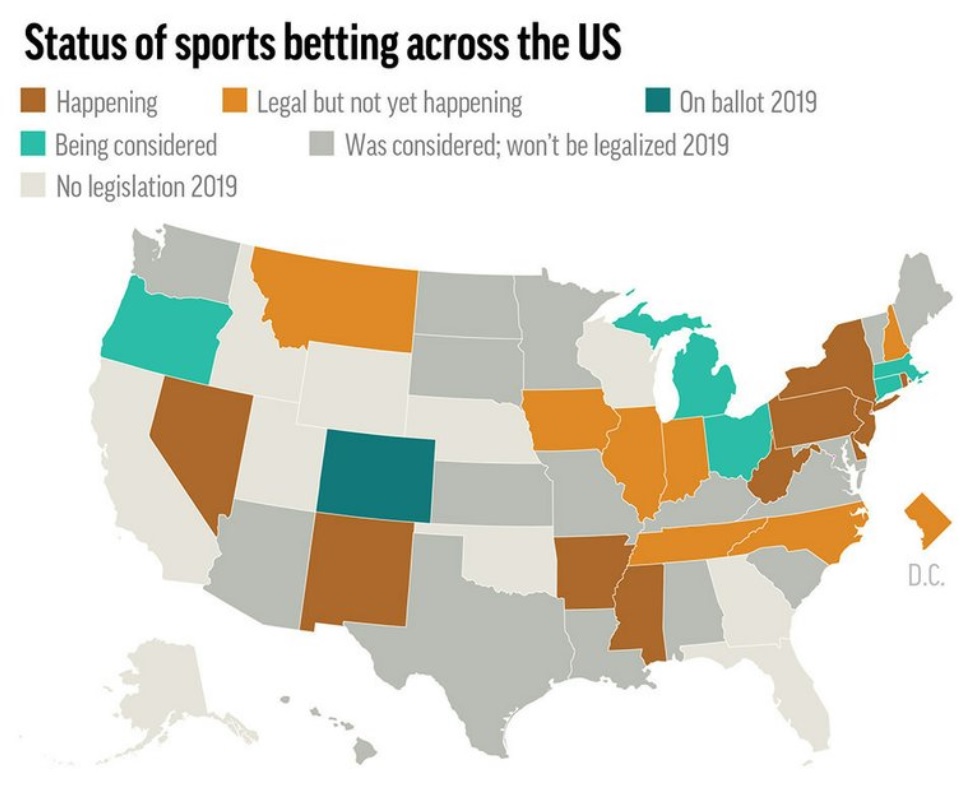

Ten states and the territory of Puerto Rico have joined Nevada in offering live, single-game betting. In the District of Columbia and seven states, wagering is authorized but not yet live, while 18 states are still grappling with legislation of sports betting. Florida and seven other states haven’t even considered it.

There is some upside. Writes the American Gaming Association’s Casey Clark, “states and sovereign tribal nations have started to build their own legal, regulated sports betting markets generating $430.2 million industrywide over the last year. This is a dramatic jump from the $261.3 million in revenue generated by Nevada alone in 2017.” (Note: Handle is a far greater sum of money, if a less reliable unit of measurement.)

How did we get here?

First, some background. In 1992, the U.S. Congress passed the Professional & Amateur Sports Protection Act (PASPA), also known as the Bradley Act after New Jersey Sen. Bill Bradley, who was a former professional basketball player. The law allowed a one-year window for states to enact sports betting or lose out forever. Nevada took advantage of this. New Jersey did not. Delaware, Oregon and Montana enacted versions of sports wagering so arcane as to be insignificant sources of revenue.

During the tenure (2010-18) of Garden State Gov. Chris Christie, New Jersey began litigating the Bradley Act, even trying to make an end-run around it by legalizing unregulated sports wagering. Neither that nor the state’s arguments made a dent with a series of federal courts … until Christie and successor Phil Murphy reached the United States Supreme Court. The arguments had little to do with handle and point spreads, and everything to do with esoteric concepts like “commandeering”: the ability of the federal government to arrogate powers that are normally the province of the state. By a 6-3 margin, the Supremes ruled that the Bradley Act was an overreach, rendering it null and void.

Immediately on Capitol Hill, not having learned from the high court’s chastisement, lawmakers began floating the idea of federal regulation of sports wagering. It was a concept that had little buoyancy. As AGA President Bill Miller told Sports Betting Operator, “I’ve been up on the Hill a lot and I’ve talked to a lot of senators, a lot of members of the House and there has been very little interest among members of the House or the Senate to take up federal legislation on this.” Indeed, that talk seems to have faded away.

As for the major sporting leagues and the NCAA, which oversees collegiate sports, they did an abrupt about face and began trying to shake down the casinos for profit participation. One gambit was to try and require casinos to get their betting data strictly from the leagues themselves. Another was to try and require “integrity fees,” a form of taxation upon sports books. “They’re 0 for 19 so far,” Miller told the Las Vegas Review-Journal. “The leagues obviously have a responsibility to run their teams with integrity, but they had that responsibility well before sports betting moved into these states. That’s why the legislators reject that argument that there be an additional fee to do what they had done previously.”

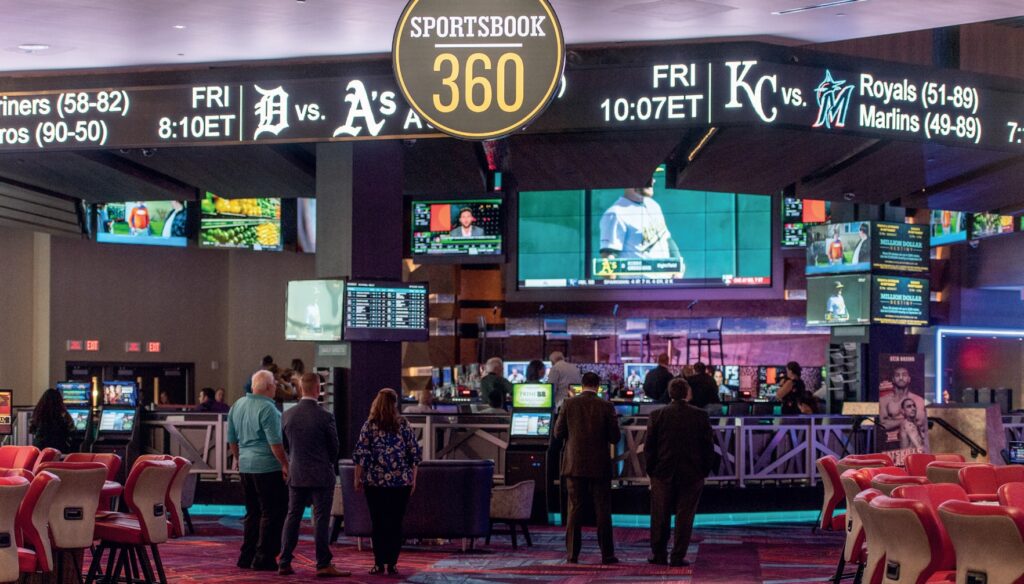

So eager were the leagues to get in bed with sports wagering that in some states, including New Jersey and Illinois, sports books are—or soon will be—embedded in professional stadiums. So, if the Chicago Cubs game is a little slow and you feel like having a bit of a flutter on the cross-town White Sox, you will be able to go up to a window in Wrigley Field and place your wager.

Dollar signs in their eyes

State governments have not been shy about taxing sports betting. However, their revenue expectations make a head-on collision with reality when hundreds of millions of dollars in handle (money bet) trickles down into a few dozen million kept (won by the books). For instance, a Super Bowl which was a foregone conclusion and generally agreed to be a dull game generated little action for the bookies, leaving all parties hurting. In New Jersey last July, the handle was $251 million but, once all players had been paid, that left only $18 million for the casinos and state to divide.

In one state, New Mexico, tribal casinos snuck through a loophole in their compacts, one that did not explicitly forbid sports betting. They have taken various approaches to this. Santa Ana Star Casino went all in while Isleta Resort & Casino was taking action strictly on intrastate matches by New Mexico collegiate teams. “There was never a hesitation … due to the fact that there are extreme measures in place in the world of betting to prevent any kind of wrongdoing that might happen,” Isleta CEO Harold Baugus reasoned to the Albuquerque Journal.

So far sports betting has made little penetration into Indian Country, partly due to the need to amend existing compacts (not the case in New Mexico) and partly due to the difficulty of bringing all parties to the table, an impasse that has already kept California’s manifold tribes from agreeing on Internet gambling. (Besides, California’s controversial card-room industry will want a piece of the action and the tribes hate the card rooms.)

Nevada’s supremacy in sports betting is momentarily being challenged by New Jersey, which has been enjoying commuter business from Pennsylvania and New York State. That will change soon, as Pennsylvania sports books sputter onto the marketplace. New York has terrestrial books at some of its casinos but will not throw up much of a challenge to New Jersey unless New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo reverses his position that mobile wagering—where the real money is—requires a constitutional amendment. “Right now, Jersey is cleaning our clock when it comes to sports betting,” lamented Assemblyman Gary Pretlow as he placed the Empire State’s first sports bet.

Cross-country rivalry

The New Jersey/Nevada contest is one that commentators like Gouker are going to enjoy stirring up as it plays out. However, the Silver State continues to hold the winning hand, with $5.2 billion of handle to New Jersey’s $3.2 billion in its first full month of legit sports betting. (Jersey does have its neighbors at a sizable disadvantage, but having most of its sports-betting infrastructure in place the moment that Christie v. NCAA was decided in the state’s favor.)

“Online sports betting is clearly the driving force in New Jersey’s sports betting market, and definitely more so than what has historically been the case in Nevada,” said PlayNJ.com analyst Dustin Gouker. So while Garden State bookies generated $251 million in July, only $38 million of that was from walk-up business. Even with only one Internet bookie on line in June, Pennsylvania saw $46 million in wagers, 42% online—and that’s with many of the casinos temporarily hors de combat.

As other states, like Iowa and Illinois, pass sports betting, they’re using it as a Trojan horse to enact bad ideas tangentially related to gambling. For instance, Iowa lawmakers revived a notion from the Clinton administration to use casinos to collect child support. Once winnings hit the “Internal Revenue Service lockdown” of $1,200, patrons would be vetted for poor credit or delinquent child support, taking enforcement out of the hands of the state and dumping it on the casinos.

While some states face disillusionment when their tax receipts come in, peer pressure is getting them to enact sports betting all the same. Latest up is Rhode Island, where Gov. Ned Lamont caved to fatigue. “I’ll revive any [gambling] idea that lets us get off the dime, and I don’t have to sit around and talk about gambling for the next three years — because in terms of my priorities, I’m not sure it’s in the top 20,” he sighed to reporters. Already two of Lamont’s biggest constituents, mammoth Foxwoods Resort Casino and Mohegan Sun, are dibbing online sports betting for themselves. And why not? That’s where the real money is.

Tally ho!

A certain beneficiary of the spread of sports betting is the horse racing industry. In the recent past it’s looked to simulcasting and “historical racing” (video-lottery terminal bets on races already run) to keep the Sport of Kings on its fetlocks. Now with the chance to offer wagering on all sports, the horsey set has cause to rejoice.

Even giddier are fans of jai alai, who predict the sport (for which betting was never outlawed) will blast off if customers can wager on individual players. The main impediment is still the dysfunctional Florida Legislature, which can’t even decide if daily fantasy sports are an acceptable form of gambling.

The AGA’s Miller thinks the burgeoning success of sports betting is a no-brainer. Touching base with the Las Vegas Sun, he said, “After experiencing firsthand the social and economic benefits that gaming brings to communities—including greater support for nonprofits and small businesses, employment and wage increases and funding for services and infrastructure—it’s no wonder that so many Americans grew to support the gaming industry’s presence. That’s why lawmakers are now moving quickly to reap the benefits presented by sports betting.”

Yes, but are they moving quickly enough? That remains to be seen.

Originally published in Sports Betting Operator Magazine October 2019