On June 14, 2018, New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy made the first-ever legal sports bets in the state’s history, plunking down 20 bucks each on Germany to win last year’s World Cup and the New Jersey Devils to hoist the 2019 Stanley Cup. Murphy would eventually lose both wagers (France/St. Louis Blues), but less than a year later he and his state hit a lucrative, historic jackpot.

For the month of May, New Jersey passed Nevada to become the top state in monthly sports betting for the first time. The Garden State harvested $318.9 million in handle (the total in bets taken) and $15.5 million in revenue (what sportsbooks earn after payouts), besting Nevada’s $317.3 million in handle and $11.6 million in revenue.

New Jersey is one of seven states, besides Nevada, that moved to allow legalized sports betting across professional and collegiate games in the year since the U.S. Supreme Court ended Nevada’s 50-year, and federally mandated, monopoly. Betting on sporting events is one of America’s favorite pastimes, even if an estimated $150 billion is wagered annually in a gray market controlled by bookies and legal offshore sportsbooks, according to the American Gaming Association.

Several factors propelled New Jersey’s rapid ascendancy, especially its well-established casino and online gambling industry. Yet it’s still too soon to know if other states can similarly cash in on legal sports betting, hailed as a big-league revenue generator to boost underfunded education, social services, infrastructure and other government programs. New Jersey, for instance, has established a Casino Revenue Fund to benefit senior citizens and disabled residents. We know for certain that more states will be trying. In five years sports betting may be available in 80% of U.S. states.

By 2024, sports betting in 40 states

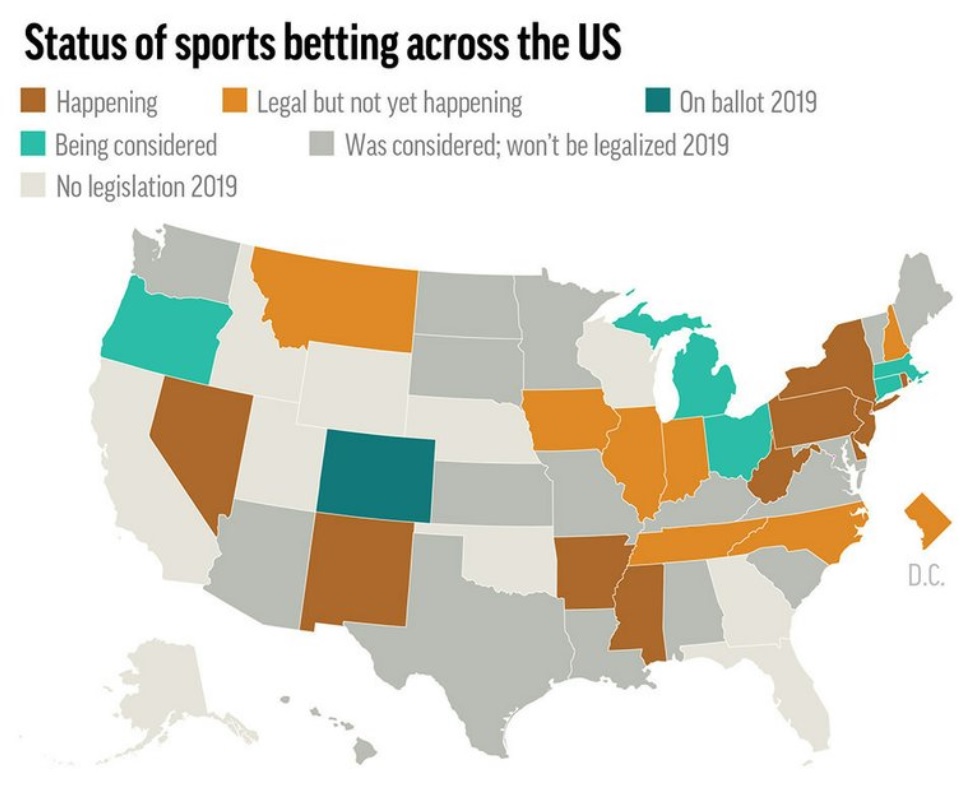

Since the unanimous SCOTUS decision on May 14, 2018, to overturn the Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act (PASPA), a 1992 federal law that had essentially restricted single-game sports betting to Nevada and its famed Las Vegas sportsbooks, legislation to authorize sports betting has either passed or is pending in 13 states.

More than two dozen other states are lining up to either consider such legislation or to activate new laws already on the books. By the end of this year, bills are expected to be considered in at least 35 states, according to Gambling Compliance, an industry research and consulting firm. By 2024, the firm estimates, as many as 40 states could allow sports gambling. Based on population, roughly 50% of Americans will live in states that have some form of sports betting by the end of next year.

By the end of last year, Delaware, Mississippi, New Jersey, New Mexico, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island and West Virginia had authorized legal sports betting. The expansion helped boost total industry-wide revenue from legal and regulated sports betting to approximately $430.2 million in 2018, up nearly 65% from $261.3 million in 2017, according to the American Gambling Association’s annual “State of the States” survey of the nation’s commercial casino industry.

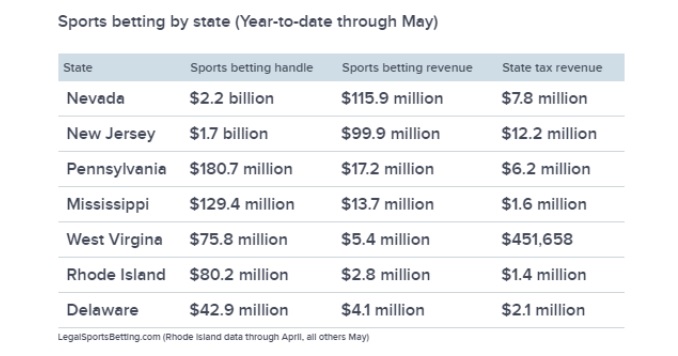

That reflects just the six months following the demise of PASPA, so revenue should jump exponentially in this and future years. So far this year, according to Legal Sports Betting’s most recent calculations, more than $4.4 billion in handle and nearly $259 million in revenue has been generated. Since PASPA was repealed, every licensed sportsbook (that has been subject to monthly reports from their states) have accumulated, for a total handle of over $8 billion, according to Legal Sports Betting. Sportsbooks in that time have kept more than $500 million, before contributing over $60 million in taxes to their respective states and cities.

Gambling Compliance projects that the legal sports betting market in the U.S. could be worth as much as $7.9 billion in total annual revenue by 2024.

Getting there can be arduous, though. Each state’s legislature must hammer out its own rules and regulations governing on-site — commercial and tribal casinos, racetracks, lottery vendors — online and mobile sports wagering, and determine licensing fees and tax rates paid by operators. In some instances a public vote or constitutional amendment may be required.

An Associated Press analysis last spring found that four of the states with newly legal operationsstill lagged well behind their estimated revenue expectations.

More from America’s Top States for Business:

Antiwar candidate Bernie Sanders faces backlash over the $1.2 trillion war machine he brought to Vermont

Colorado grows annual cannabis sales to a billion dollars, as other states struggle

The most expensive places to live in America

Despite the outburst of competition over the last year and a half, Nevada still raked in a record $301 million in sports betting revenue; the seven newbie states combined for $129.6 million. From January through April of 2019, Nevada’s sportsbooks registered $1.88 billion in handle and $104.6 million in revenue.

“As you can see from our numbers, Nevada continues to be the market leader in sports betting,” Sandra Douglass Morgan, chairwoman of the Nevada Gaming Control Board, said in an email statement to CNBC. The PASPA decision, she added, has not had a negative impact on Nevada’s sports betting industry.

Although New Jersey surpassed Nevada for May, it should be noted that the two states report their handles a bit differently. Jersey’s numbers include bets on future events, such as this fall’s World Series, before they are paid out. Nevada doesn’t count future bets until they’re paid.

What portion of the revenue earned by sports betting operators that ultimately trickles down to state coffers to fund legislatively earmarked programs widely varies, largely depending on tax rates. Delaware and Rhode Island, for example, tax roughly 50% of operators’ monthly revenue; Pennsylvania has a 34% rate. Mississippi collects an 8% state tax and a 4% local tax, while New Jersey levies an 8.5% tax on land-based operators and 13% from online and mobile platforms, plus an additional 1.25% tax from all sources for Atlantic City marketing efforts.

Nevada, which legalized casino gambling in 1949, imposes a 6.75% tax on all betting activity, including sports. And although every state in the union, except Hawaii and Utah, regulates some form of legal gambling, Nevada still dominates the industry. The Silver State reported $11.92 billion in commercial casino gaming revenue last year, a 3% increase from 2017, with Las Vegas accounting for $6.59 billion.New Jersey’s quick win

That may continue, factoring in Nevada’s event-based supremacy, especially with inordinate betting around the Super Bowl and March Madness. But for the time being, New Jersey’s shrewdly built gambling business has made the sportsbook entry a win.

The state ushered in legal casino gambling in Atlantic City in 1978, then authorized internet gambling in 2013. Jersey’s attempts to authorize sports betting began in 2009 under then-Gov. Chris Christie, but that plan was thwarted when the four major pro sports leagues and the NCAA sued, citing PASPA and the potential for corrupting the integrity of their games. A series of court battles culminated with the SCOTUS ruling, and Jersey was soon off to the races.

The first online/mobile sportsbooks in New Jersey went live last August. More than 80% of bets placed in the Garden State occur digitally, as explained on Legal Sports Report’s website, giving easy access to New Jersey, Pennsylvaniaand New York residents. Bettors can sign up for and fund accounts remotely — a major advantage Nevada regulators refuse to consider under pressure from local casinos — although they must physically be within the state.

Another element pacing New Jersey’s rise is bettors’ prolific use of sports betting apps, including FanDuel Sportsbook and DraftKings Sportsbook, offshoots of their fantasy sports betting platforms that were already immensely popular among sports gamblers, making the transition relatively simple.

Only New Jersey and Delaware were on a path to meet their projections, the latter with help from a long-running football parlay game operated by the state’s lottery. Earlier this year, Rhode Island and West Virginia were bringing in less than a quarter of the amount needed each month to hit their projections, the AP reported. Mississippi was on pace to bring in a little more than half what officials predicted, and it was estimated that Pennsylvania would realize about two-thirds of expected revenue.

In response, Allen Godfrey, executive director of the Mississippi Gaming Commission, said his agency “does not make projections of revenue,” although he believes the state’s Department of Revenue set an estimated benchmark of $5 million when legislators requested one. Godfrey expects tax revenue will be closer to $3.8 million this fiscal year, but more importantly, gross gaming revenue will be up almost 5%, to about $42 million, an increase he attributes to sports betting.

“Sports betting is not about the [tax] revenue it generates,” he said, “but about additional foot traffic and benefits to properties in additional gross gaming revenues.”

Rhode Island relied on industry consultants to develop a feasible initial estimate, Paul Grimaldi, a spokesman for the Department of Revenue, wrote in an email, though he did not provide a specific figure. “The latest analysis we’ve received indicates that our estimation is achievable, though it will take longer than expected for the market to mature.” Ultimately, he said, “sports betting will produce new revenue for the state — and, by extension, our partners in casino operations.”

“Any kind of sports betting is a low-margin product and requires high volumes for the revenue to get there,” said Chris Grove, managing director at Eilers & Krejcik Gaming, an Irvine, Calif.-based firm that researches gambling. “The good news is, it’s a high-volume product. There’s substantial demand.”

Grove said there’s “really no value in comparing tax projections to receipts at this point. Sports betting revenue is highly variable, and a bad run on one marquee event such as the Super Bowl can dramatically distort returns. Regulated sports betting is a long game. I would expect a typical state to take around four years before it starts to get to that baseline maturity level.”

Concerns about compulsive gambling

Beyond economics, opponents of sports betting worry about a proportional uptick in problem gambling as legal wagering proliferates. The gaming industry spends $300 million annually on responsible gambling initiatives nationwide, yet the spending remains inconsistent and no programs currently exist to ensure accountability, the American Gaming Association’s annual report states.

The National Council on Problem Gambling in Washington works with state and national gaming officials to develop programs and services to deal with the issue. Executive Director Keith Whyte is concerned about the growing ease of sports betting, particularly on mobile devices. “We believe that unless aggressive, responsible gambling measures are put into place, the prevalence and severity of problems will increase,” he said. Some states have done a good job of investing in comprehensive programs, while others have done little, he added.

Whyte singled out New Jersey as the leader, backed by data-driven programs and experienced regulators. Conversely, he cited Mississippi for its paucity of state funding for combating problem gambling. “Its regulations are minimalist at best,” Whyte said, “and without dedicated money, they have a very poor system.”

Mississippi “does not dedicate any money solely to compulsive gambling,” Godfrey said. The Gaming Commission’s budget used to earmark $110,000 annually to the state’s Council on Problem and Compulsive Gambling, “but that was removed. So the council is dependent on raising their own funds.”

Regardless of such concerns, Grove expects that the scramble to gamble will continue.

“Roughly 50% of the U.S. population will live in states that have some form of sports betting by the end of next year,” he said. The primary obstacle will be getting all stakeholders on the same page about the best way to offer it, who controls it and how the revenue is distributed.

“The more voices you have singing their own melody, the rougher it is to get a chorus.”