‘A LEVEL PLAYING FIELD’ By Marc Zwillinger & Ben MacLean

Event contracts are understood as a type of commodity. Although commodities are traditionally known as tools to hedge economic risk over agricultural futures like soybeans or cotton, financial innovation (and litigation resulting from such innovation) has helped spread these tools to new areas, including sports. As of today, designated contract markets (DCMs) can provide sports-event contracts to consumers in all 50 states.

This position is both unsettled and controversial with states attempting to push back on this development both demanding that operators cease and desist operations in their states, and pleading with the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) to disallow event contracts that too closely resemble sports betting. These efforts are based in no small part on the reasoning that DCMs do not operate within the same regulatory regime followed by sports book operators to protect the integrity of sporting events, guarantee payments to bettors and seek to mitigate effects on those susceptible to the addictiveness of gambling or gambling-like conduct. But courts, for now, seem to be siding with DCMs … at least until the CFTC, if ever, makes clear whether it views sports-event contracts as permissible on its markets.

In April 2025, federal courts in Nevada and New Jersey granted a DCM named Kalshi a preliminary injunction against those states’ respective gaming regulators, enjoining them from enforcing state gaming laws against Kalshi’s CFTC-regulated event contracts. The courts found that the Commodity Exchange Act (CEA) preempts state attempts to regulate contracts traded on a CFTC-designated exchange. They also ruled that Kalshi had shown a likelihood of success on the merits, irreparable harm, and that the balance of hardships and public interest favored injunctive relief. As the courts noted, “Because the CFTC has approved (or at least not yet disapproved) Kalshi’s sports-related contracts, the defendants cannot pursue civil or criminal liability against Kalshi for offering those contracts.”

Image: Ben MacLean is a fellow at ZwillGen PLLC

Nationally, the current administration has generally embraced deregulation policies. But sports-event contracts are a complicated topic that demand a more nuanced approach. Despite the purported hedging, economic, and informational value of these contracts, open questions remain on both legal and policy fronts. For example, does purchasing a sports-event contract implicate prohibitions on gambling under federal or state law? Does the federal agency responsible for commodities have exclusive jurisdiction over sports-event contracts? Are there consumer protection principles that should be at play here?

The CFTC recently canceled its planned roundtable to explore these issues and the future remains uncertain. Below, we discuss the legal and policy considerations surrounding sports-event contracts.

What Are Event Contracts?

Event contracts are a type of derivative contract whose payoff is based on a specified event, value or occurrence (known as an “underlying”) that is “(1) beyond the control of the parties to the relevant contract … and (2) associated with a financial, commercial, or economic consequence.”2 Event contracts function as binary yes/no options with fixed payouts and are traded on DCMs subject to oversight by the CFTC, an independent federal agency responsible for protecting the U.S. derivatives market.

The subject of an event contract can vary widely. For example, a DCM can list contracts such as, “Will the price of eggs go up this month?” or “Who will win the men’s NCAA March Madness tournament?” The price of each contract generally demonstrates the market’s determination of whether an event will occur, and contracts generally settle at $1 each. So if the price of a “yes” contract was $0.60, that would show (a) that the likelihood of the answer being “yes” is around 60%, and (b) that you would be paid $0.40 on top of your $0.60 investment if you are right (minus whatever fee the DCM charges, of course).

What Laws Impact Sports- Event Contracts?

This is a question that is constantly evolving. Most DCMs take the position that the CEA provides the CFTC with exclusive jurisdiction over event contracts, regardless of their underlying. However, this is disputed by a number of tribes, state regulators and other interested parties. Below, we discuss various legal authorities in addition to the CEA that may impact sports event contracts.

-

The Commodity Exchange Act

The CEA, as amended by the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform & Consumer Protection Act of 2010, provides a “comprehensive regulatory structure” for commodity and futures trading.3 Under the CEA, DCMs can self-certify that an event contract meets all applicable CEA and CFTC rules and promptly list the contract for trading.

A section of the CEA known as the “Special Rule” gives the CFTC discretion to review and prohibit event contracts that it determines are “contrary to the public interest.”4 Contracts are contrary to the public interest if they involve “activity that is unlawful under any Federal or State law,” “terrorism,” “assassination,” “war,” “gaming” or “other similar activity determined … by rule or regulation to be contrary to the public interest.”5 After a DCM self-certifies a contract, the CFTC can initiate a 90-day window to determine whether it is contrary to the public interest. “Gaming” under the Special Rule was previously interpreted to encompass a broad range of activities, giving the CFTC considerable authority to prevent contracts that appeared to be contrary to public interest.

For instance, in 2012, the CFTC ordered the North American Derivatives Exchange, a DCM, to stop allowing users to purchase political event contracts based on whether there would be a Democratic/Republican majority in the U.S. House of Representatives or Senate. Looking to the Special Rule, the CFTC ruled that because “several state statutes, on their face, link the terms gaming or gambling … to betting on elections, and state gambling definitions of ‘wager’ and ‘bet’ are analogous to the act of taking a position in the Political Event Contracts,” the contracts involve “gaming” under the Special Rule and are contrary to public interest.

Image: Marc Zwillinger, founder and managing member of ZwillGen PLLC

In 2021, the CFTC similarly proposed an order for DCM ErisX to stop listing event contracts involving the money line, point spread and total points on NFL football games. The order, which was not published due to ErisX’s voluntary withdrawal of the contracts, would have found that the contracts involved gaming and were contrary to the public interest. However, then-commissioner Brian Quintenz issued a lengthy statement explaining that he would have dissented, due to concerns about the Special Rule’s constitutionality.7 Quintenz wrote that there are significant differences between betting and derivatives speculation: Whereas there is no economic utility in games of chance, derivatives market speculators participate in “non-chance driven outcomes that have price-forming impacts upon which legitimate businesses can hedge their activities and cash flows.” Quintenz also opined that the Special Rule is unconstitutional due to the grant of discretion to the CFTC to effectively ban any contract through arbitrary public-interest determinations.

“WE NEED TO CALL AN OFFICIALS’ TIME-OUT, GO TO THE REPLAY BOOTH, RESET THE CLOCK AND ENSURE THAT THE GAME IS BEING PLAYED ACCORDING TO THE RULES OF THE CONSTITUTION. THAT WOULD TRULY BE ‘IN THE PUBLIC INTEREST.’”

FORMER CFTC COMMISSIONER BRIAN QUINTENZ, MARCH 25, 2021

Following Quintenz’s tenure as commissioner at the CFTC, he served as an advisory council member at Crypto.com, a board member at Kalshi and the head of policy at venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz.

In 2024, the CFTC sought to enforce the Special Rule against Kalshi. The latter offered event contracts based on the outcome of U.S. congressional elections, which the CFTC alleged was “gaming” or unlawful under states’ laws and therefore contrary to the public interest. Kalshi sued the CFTC, challenging its decision on the grounds that it was arbitrary, capricious and not in accordance with the Administrative Procedure Act.8 In that suit, Kalshi acknowledged that “gaming” involved sporting events but not elections. The U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia ruled in Kalshi’s favor and agreed that elections were not subject to the Special Rule as they were not illegal activities or gaming. The district court held that “gaming requires a game,” such as sports or games for stakes, like poker. A contract “involves” an activity contrary to public interest if the underlying relates to that activity – to consider all event contracts “gaming” when based on an undetermined event would inundate the Special Rule’s structure because all event contracts would be affected.

The CFTC initially appealed this decision to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, but later moved to voluntarily dismiss it following Donald Trump Jr.’s appointment as a “strategic advisor” to Kalshi and Quintenz’s nomination to lead the CFTC as its chairman. Kalshi, for its part, now takes the position that while sporting events may be within the definition of “gaming” for purposes of the Special Rule, the CFTC’s failure to initiate a review means that the contracts are valid under the CEA.9

-

The Interstate Wire Act

The Interstate Wire Act of 1961 (Wire Act)10 is the principal applicable federal law restricting sports betting. The Wire Act prohibits those in the “business of betting and wagering” from knowingly using a “wire communication facility” for transmitting interstate or foreign bets or wagers or information assisting the placing of bets or wagers on sporting events or contests. While other federal laws, such as the Unlawful Internet Gambling Enforcement Act of 2006,11 contain an explicit exception for activities regulated by the CEA, the Wire Act has no such exception.

iii. The Wire Act does not directly define what “bet” or “wager” entails, but courts interpreting the statute have enforced it in scenarios that could potentially apply to sports-event contracts.12 It is uncertain where a court might draw the line if it were asked to make this determination, however, and state laws make this area even murkier. On one hand, DCMs are providing users the means to stake money on the outcome of a sports event. On the other, there is real utility in hedging risk on events with legitimate economic impact, and courts could view all contracts traded on a CFTC-regulated exchange as categorically non-gambling.

State Laws

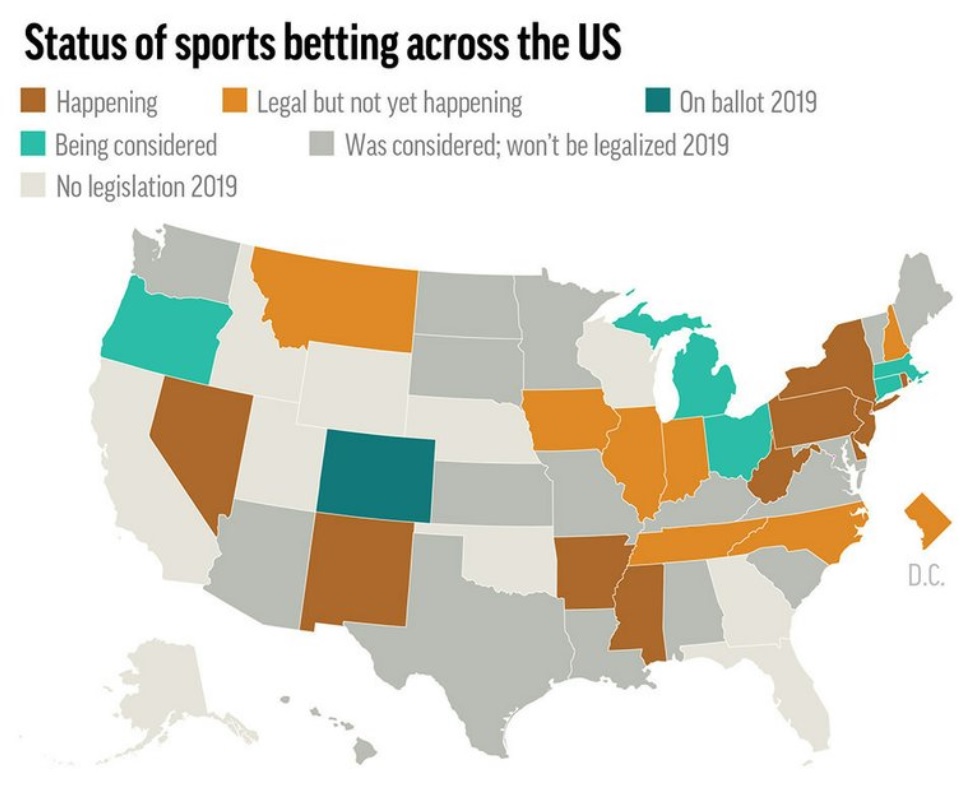

Sports betting – and broadly, gambling – is a topic primarily left to the states as part of their police power to regulate for the public welfare. Since the Supreme Court struck down the Professional & Amateur Sports Protection Act (PASPA) in 2018 on 10th Amendment grounds, sports betting is now legal in 38 states. Each state that has legalized sports betting has strict requirements for operators to comply with applicable consumer-protection and licensing requirements. Failure to comply can result not only in civil penalties but even in jail time.

Under state law, wagering or gambling is commonly defined as risking a sum of money on chance or a future contingent event. When the CFTC recently announced its intent to hold a roundtable on prediction markets and sports-event contracts, numerous industry associations, tribes, and interested parties wrote to express their concern about the impact on states’ roles as regulators. For example, the American Gaming Association explained that to allow sports event contracts to operate in all 50 states would “circumvent[] the important regulatory protections implemented by states, … [and] raise the prospect of considerable consumer and marketplace harms.”13 Among the common protections that these commentators cited are age verification, anti-money laundering, integrity monitoring and self-exclusion measures, among others. States also stand to benefit from protecting tax revenues from regulated sports betting. In 2023 alone, states collected nearly $2 billion in sports betting tax revenues.14

States are beginning to take the potential encroachment on their ability to control the sports betting market and the resulting potential loss in tax revenue seriously. At the time of this writing, seven states have publicly announced regulatory investigations, with more rumored to be on the way. From states’ perspectives, sports event contracts run afoul of state licensing requirements and related sports betting regulations. Nevada and New Jersey were the first two states to send cease and desists to Kalshi, which subsequently sued in late March seeking injunctive relief. On April 9, the Nevada District Court granted Kalshi’s motions for a temporary restraining order and preliminary injunction, ruling that the company is exclusively subject to federal CFTC regulation as a CFTC-designated DCM. On April 28, the New Jersey District Court ruled the same way, pulling heavily from the Nevada District Court’s reasoning. It’s possible that future decisions on the matter will reach the same conclusion, but the defeats in Nevada and New Jersey have led to states attempting to assert that Congress’s passage of federal gaming laws (the Wire Act, the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act and PASPA) show that the CEA was not intended to pre-empt state gaming laws.

What Lies Ahead for Sports-Event Contracts?

It is critical that the correct balance of regulation is struck that protects consumers while allowing businesses to mitigate risk. It is a distinct possibility that event contracts are completely outside the scope of state regulation, but there are some potential downsides to this outcome. The CFTC may have exclusive jurisdiction over commodities, regardless of their underlying. But if the CFTC doesn’t make a distinction between contracts with significant economic impact (e.g., winner of Super Bowl, World Series, etc.) and those without (e.g. winner of individual games, individual player performance), it runs the risk of turning event contracts into a substitute for sports betting but without the protections that states have endeavored to create. It is easy to see how high-stakes sporting events like the Super Bowl could have an economic impact on a city.15 However, it is more challenging to see a significant economic impact from run-of-the-mill individual games or player performances. These lower-stakes offerings, combined with a lack of regulation, could undermine the effort to keep sports events contracts under the CFTC’s jurisdiction.

States commonly legislate requirements that involve protections for problem gamblers, game-integrity assurances, marketing and advertising restrictions, and more. The CFTC has not addressed these requirements in the past, yet these are important concerns that must be accounted for. A number of state regulators, including those from Illinois, Tennessee, Maryland, Michigan and Pennsylvania submitted letters to the CFTC objecting to the operation of sports event contracts within their jurisdictions. In particular, the Tennessee letter argued that contracts offered by CFTC-regulated platforms are indistinguishable from unlicensed sports betting. The letter also details how such offerings sidestep age verification, AML rules and responsible-gambling protections – stating bluntly that these contracts are “being offered in violation of Tennessee law and regulations” and that CFTC-regulated entities are “not compliant with these protections (or many others) mandated by the Tennessee Legislature.”16

DCMs often emphasize that consumers are merely “predicting” rather than “betting” on sports events, yet studies have increasingly observed a link between problem gambling and online trading products.17 Should the CFTC fail to act here, it is easy to foresee the consumer and market harms that may occur. The National Council on Problem Gambling perhaps said it best in its letter to the CFTC:

State and tribal regulators are experienced in regulating sports gambling. They are constantly updating their regulations and guidance to include best practices and work to balance the benefits of gambling revenue with the costs of gambling-related harm. Given this, the CFTC should either acknowledge state and tribal prerogatives or create a regulatory framework that also prioritizes players’ health. If the CFTC determines that it does not have the authority to require truly robust responsible-gambling measures and problem-gambling safeguards on par with state and tribal regulators, it should not allow these markets.18

By striking a balance between consumer protection and innovation through clear guidelines that prioritize consumer protection, the CFTC can ensure sustainable growth in this market for years to come.

Conclusion

The CFTC must establish clear rules on what is acceptable for sports-event contracts and develop a regulatory framework that addresses both business-hedging interests and the consumer-protection measures that states have created. Collaboration with state regulators can ensure that the market remains fair, transparent and safe for all without stifling innovation.

** This article was originally published in July 2025 edition of Sports Betting Operator Issue 017.

1 Order Granting Kalshi’s Motion for Preliminary Injunction, KalshiEX LLC v. Hendrick et al., No. 2:25-cv-00575-APG-BNW at *6 (D. Nev. Apr. 9, 2025); See Opinion Granting Kalshi’s Motion for Preliminary Injunction, KalshiEx LLC v.Flaherty et al., No. 25-cv-02152-ESK-MJS at *10 (D.N.J. Apr. 28, 2025).

2 7 U.S.C. § 1a(19)(iv).

3 Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner & Smith v. Curran, 456 U.S. 353, 356 (1982); See 7 U.S.C. § 2(a)(1)(A).

4 7 U.S.C. § 7a-2(c)(5)(C)(i).

5 Id.

6 In the Matter of the Self-Certification by North American Derivatives Exchange, Inc., of Political Event Derivatives Contracts and Related Rule Amendments under Part 40 of the Regulations of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (Apr. 2, 2012).

7 Any Given Sunday in the Futures Market, Statement of Commissioner Brian D. Quintenz on ErisX RSBIX NFL Contracts and Certain Event Contracts (Mar. 25, 2021), https://www.cftc.gov/PressRoom/SpeechesTestimony/quintenzstatement032521.

8 KalshiEX LLC v. Commodity Futures Trading Comm’n, No. CV 23-3257 (JMC), 2024 WL 4164694 (D.D.C. Sept. 12, 2024).

9 See Plaintiff’s Motion and Memorandum of Points and Authorities in Support of an Immediate Temporary Restraining Order and Preliminary Injunction, KalshiEx LLC v. Hendrick, et al., Docket No. 2:25-cv-00575 *10(D. Nev. Mar. 28, 2025); See Plaintiff’s Motion and Memorandum of Authorities in Support of a Temporary Restraining Order and Preliminary Injunction, KalshiEx LLC v. Flaherty, et al., Docket No. 25-cv-2152 *20 (D.N,J. Mar. 29, 2025).

10 18 U.S.C. §§ 1081–1084.

11 31 U.S.C. §§ 5361–5367.

12 See e.g., U.S. v. Cohen, 260 F.3d 68 (2d Cir. 2001); U.S. v. Kelley, 395 F.2d 717 (2d Cir. 1968).

13 Letter Re: Prediction Markets Roundtable, American Gaming Association (Feb. 20, 2025), https://www.cftc.gov/media/11791/AmericanGamingAssociation022025/download.

14 Adam Hoffer, Bets on Legal Sports Markets Pay Off Big for States, Sportsbooks, and Consumers, Tax Foundation (Dec. 10, 2024), https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/state/sports-betting-tax-revenue/.

15 How the Super Bowl Creates Economic Impact Across the Country, U.S. Chamber of Commerce (Feb. 6, 2025), https://www.uschamber.com/economy/how-the-super-bowl-creates-economic-impact-across-the-country (“The final estimated local economic impact of last year’s Super Bowl in Las Vegas was $1 billion – fueled by direct spending by visitors and residents, indirect spending at local businesses, employment, and tax revenue.”).

16 Letter from Mary Beth Thomas, Executive Director, Tennessee Sports Wagering Council, to CFTC Acting Chair Caroline Pham (Apr. 14, 2025).

17 M. Mosenhauer, P.W.S. Newall, L. Walasek, The stock market as a casino: Associations between stock market trading frequency and problem gambling, J Behav Addict 10(3) (2021) http://dx.doi.org/10.1556/2006.2021.00058; A. Oksanen, E. Mantere, I. Vuorinen, I. Savolainen, Gambling and online trading: emerging risks of real-time stock and cryptocurrency trading platforms, Public Health 205 (2022) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2022.01.027; U. Lee, L.E. Lewis, D.J. Mills, Association between gambling and financial trading: A systemic review F1000Research (2023) https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.129754.1.

18 Letter Re: Prediction Markets Roundtable, National Council on Problem Gambling (Mar. 10, 2025), https://www.cftc.gov/media/11956/NationalCouncilonProblemGambling031025/download.