College sports’ first major foray into the sports betting world could lead to far-reaching tax and intellectual property issues to contend with down the road, lawyers say.

The five-year, $1.625 million agreement between the University of Colorado and sports betting operator PointsBet, the details of which were first reported by Bloomberg Tax on Friday, is the latest in an explosion of ad-deals between sportsbooks and teams or leagues, although it’s the first collegiate pact of its kind.

Limiting advertising to neutral sponsorship statements ensures the university won’t pay taxes on the deal. That could be a game changer for athletic departments hemorrhaging funds during the pandemic.

But the partnership—which secures the university extra revenue for every new PointsBet customer linked to one of the ads it displays—opens the door for more and perhaps broader deals between bookmakers and college sports.

“The issues are going to be rushed from the back burner to the front burner very quickly, as more and more deals like this come to light,” said Baird Fogel, a partner at Morgan Lewis & Bockius LLP in San Francisco, who heads the law firm’s sports betting group. “The only reason why this isn’t everything everybody’s talking about is because of Covid-19.”

The NCAA has historically opposed sports betting, even after the Supreme Court opened the door for states outside of Nevada to regulate and tax the industry in 2018. Just this summer, members of the Atlantic Coast Conference—one of the NCAA’s premier athletic divisions—asked Congress for a federal ban on college sports betting.

At the same time, PointsBet and the University of Colorado were putting the finishing touches on their agreement, said Johnny Aitken, PointsBet’s CEO of U.S. operations, who called it “a great blueprint” for potentially working with other schools in the future.

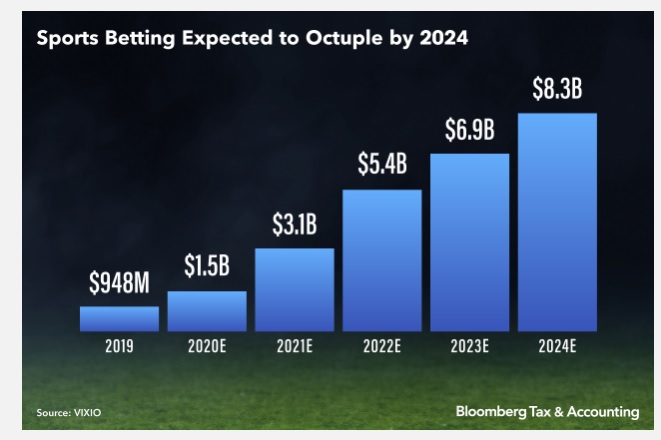

“This could pave the way for more schools and the NCAA to share in some of the sports betting revenue stream, which is in the billions,” Fogel said.

“It’s shocking, because just a few years ago—even just a few months ago—a relationship like this seemed impossible,” Fogel said.

Colorado called the deal an opportunity to stop some of the financial bleeding in its athletic department caused by the coronavirus pandemic. The agreement was announced last month, and the school’s athletic director said the NCAA approved; Bloomberg Tax obtained the deal’s parameters on Oct. 2.

“It’s possible the NCAA in light of this is going to say, ‘Well, we need money ultimately, and times are changing,’” said Radney Wood, a partner at Vela Wood in Austin, Texas. “If that’s the case, other schools will definitely start following suit.”

Tax Break

The University of Colorado will likely pay zero taxes on the $1.625 million, thanks to narrow language around how PointsBet gets advertised.

While most public universities are exempt from paying taxes, they do owe the IRS for regularly carried on business unrelated to their core mission. These activities—classified as unrelated business taxable income (UBTI)—include earnings from things like football tickets and concession stand sales.

The PointsBet deal should avoid this tax, as it seems to meet IRS guidelines for a qualified sponsorship agreement, and is limited to neutral statements about the product, said Alex Reid, a partner at Morgan Lewis & Bockius LLP in Washington, D.C.

“You can say, ‘Thank you very much to our exclusive soft drink partner, Coca-Cola,’” explained Reid. “But you can’t say, ‘Coke is better than Pepsi.’”

Just $1,231 of the university’s advertising profit was taxable in 2018, according its latest available tax returns.

“Arranging deals like this isn’t difficult,” said Samuel Brunson, a tax professor at Loyola University Chicago School of Law.

Under the IRS guidelines “there’s a special code section, § 513(i), that shields tax-exempt organizations like the NCAA from tax on sponsorship income,” said Reid, who explained that taxable organizations would “generally be taxed at corporate tax rates, currently 21%.”

As long as there’s no expectation that PointsBet will receive a “substantial return benefit other than the use or acknowledgment of its name or logo (or product lines),” and the university avoids qualitative statements in its advertising, the sponsorship should meet tax-exempt requirements.

“The institution can say, ‘We’re not getting into the gambling business. We’re simply accepting charitable assistance in return for goodwill advertising,’” Reid said.

Support for Students

Annually, $75,000 from the deal will go to “support the development of student athletes and PointsBet recruitment,” a portion of which is tax deductible for PointsBet.

The sponsorship agreement gives PointsBet access to student athletes to “promote future internship and job placement” as well as room at career fairs and permission to develop recruitment events.

Kendall Spencer, former chair of the NCAA’s National Student-Athlete Advisory Committee, was skeptical.

“What’s most troublesome here is the student athletes don’t have any opportunity to take a look at the deal,” said Spencer, who studies law at Georgetown University. “You can talk about it feeding into career development, but the lawyer side of me says they have to define that.”

Pandemic Play

The pandemic has forced some schools to eliminate sports. In July, Stanford announced the end of 11 varsity programs, citing “harsh new financial realities imposed by Covid-19.”

Stanford didn’t say how much money it’s lost from the pandemic, but major college sports is big business. The University of Colorado spent $98.4 million on athletics in the 2018-2019 season, a spokesperson told Bloomberg Tax.

“PointsBet is very smart to start to get into this business when the whole college sports industry is in this gray area right now,” said Jaime Miettinen, a sports lawyer and founder of Miettinen Law PLLC in Michigan.

The deal is likely the biggest, but not technically the first, between a gambling company and university. Shortly after PointsBet and Colorado made their announcement, William Hill, a London-based bookmaker, revealed it has had a small marketing partnership with the University of Nevada since 2017. Sports betting has been legal in Nevada since the 1940s.

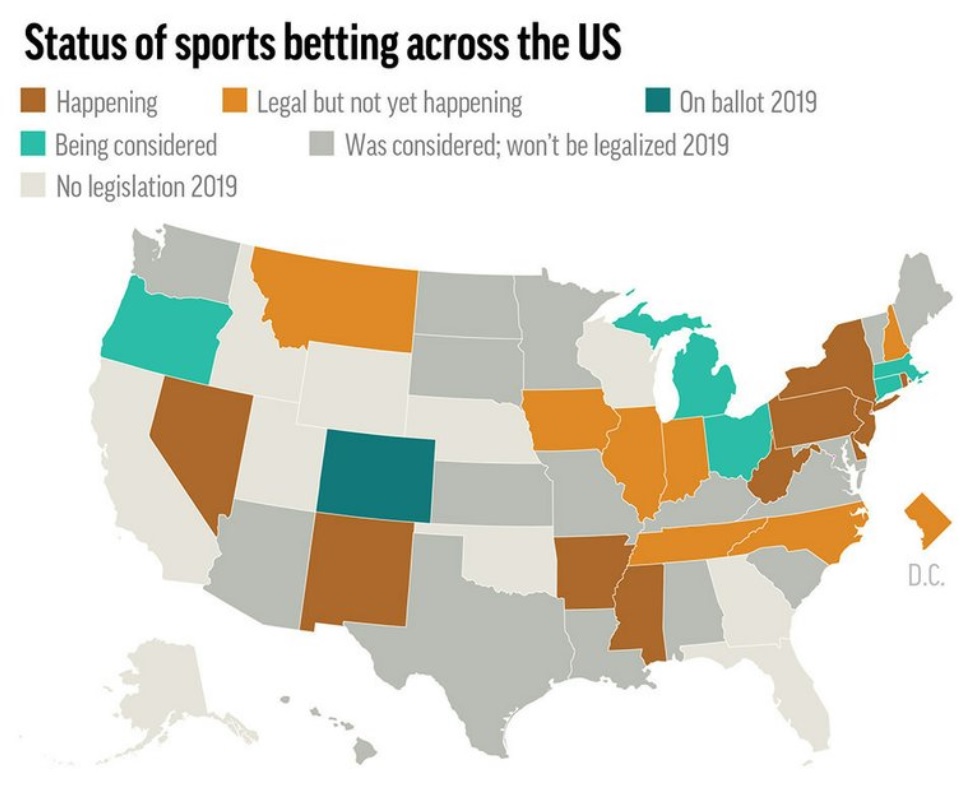

States have taken in a sizeable share of the billion dollar revenue stream. Last year sports betting—which is now legal in 18 states and the District of Columbia—brought in $118 million in taxes across 14 states.

Colorado, which launched operations in May, has already generated $744,890 from taxing the industry.

Bridge to ‘Real Currency’

With its announcement, Colorado joined professional counterparts like the NFL and MLB, which have deals with gambling companies. Many of those partnerships go beyond advertising however, and incorporate a lucrative exchange of data on player stats and injury information, which helps oddsmakers set lines.

The NFL reported $1.47 billion in sponsorship revenue last last year, a 6% increase from the previous year, which many observers attribute to its adding sportsbook sponsors for 21 teams.

The Colorado-PointsBet deal “doesn’t include PointsBet getting access to real-time data directly from CU for their games,” Aitken told Bloomberg Tax. “The data element is very fractured at the moment in the U.S. college space. We’ll see how that plays out over the coming year.”

But future collegiate partnerships with sports bettors could be more like professional leagues, said Fogel, who called data the “real currency” of sports betting.

“That is probably where it’s headed,” Fogel said. “There are a number of sports data companies running around right now and very quickly trying to secure relationships with conferences and universities.”

And that could be a much bigger deal for student-athletes—especially if they are uncompensated.

Data Dilemma

“It could cause an uproar if injuries and personal issues were shared,” said Joshua Gaddy, a former wide receiver for the University of Buffalo. “A lot of these guys don’t have much money. You have to remember these are 18-, 19-year-old kids, most of whom don’t come from much.”

’The NCAA has its own data collection partnership, although it is limited to licensing scores to media platforms and providing coaching insight to schools. Member institutions were offered the technology in 2018, but haven’t been public about signing deals.

Some states like Michigan, Tennessee, and Illinois mandate the inclusion of official league data in their sports betting laws.

If schools start selling data it’ll likely be tax-free, according to Reid. But athletes could make the case that “they should have some sort of share in it,” according to Miettinen.

Several students already have sued the NCAA over its monopoly on their name, image, and likeness—an issue the NCAA has promised to sort out by January.

“They’re also going to make some sort of proprietary claim as to the actual IP related to this data, because, in truth, they’re the ones that actually produce it—from being injured to gaining stats in the game,” Fogel said. “Obviously, the schools have proprietary interest in it as well, as does the NCAA.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Sam McQuillan in Washington at smcquillan@bloomberglaw.com